Cut A Rug

“Noam Chomsky has

described the contemporary Republican Party as ‘the most

dangerous organization in human history’.” – Joseph

O’Neill, ‘Save the Party, Save the World’, New York

Review of Books, August 20, 2020.

“Why do you think I

have chosen solitude? Commerce with men is a dangerous

business. The only way I have found to avoid being betrayed

is to live alone.”

– Jean-Pierre Melville.

One week

prior to the most significant US Presidential elections in

decades, local denizens of Lower Hutt’s Moera Hall were

treated to Wellington-based bluegrass band T-Bone’s broad

canvas of musical styles, including tinges of bluegrass,

old-time, country, cajun, and zydeco influences. They

currently comprise a multi-instrumental acoustic quintet who

share an obvious passion for painting with an effervescent

and polychromatic palette. The result is an accomplished

blend of high-octane Americana music with fiery solos on

guitar, mandolin, banjo, bass, and fiddle, and close vocal

harmonies on their slower, more melancholy tunes.

Since

getting together in 2005, T-Bone have appeared at numerous

Antipodean folk festivals, as well as the 2015 Rainforest

World Music Festival in Sarawak, Borneo. Alongside Aaron

Stewart, Cameron Dusty Barnell is multi-instrumentalist,

singer, and songwriter who has toured extensively with The

Frank Burkitt Band, The Federal String Band, The Hardcore

Troubadours, and as one half of the duo Kim and Dusty. Gerry

Paul is an award-winning songwriter, musician, and producer,

as well as a highly respected session musician who has

performed and recorded with Grammy Award winning bluegrass

icon Tim O’Brien, Irish platinum-selling accordion maestro

Sharon Shannon, and Bansoori player Ravi Kumur, as well as

with his own band Gráda. Largely self-taught fiddler,

Richard “The Pimp” Klein is a connoisseur of fine wines

from New Jersey, best known for his previous collaboration

with Melbourne’s Le Blanc Brothers Cajun Band.

There has

perhaps never been a more polarizing or argument-provoking

genre of music than bluegrass, a development of American

roots music that derives its name from Bill Monroe’s

pioneering band, The Blue Grass Boys, and flowered in the

1940s. Traditionalists insist it has to include a banjo,

mandolin, guitar and bass, with three-part harmonies and

maybe even a bass fiddle thrown in, but certainly no

amplified bass or drums. While some believe the rapid growth

of the jam band scene has hurt bluegrass, others think

musicians like Allison Krauss have converted the genre from

the gutsy, ballad-spewing, breakneck tempo music that it was

into the wispy, AM-gold, elevator music that much of it has

become. Or maybe The Berklee School of Music is to blame,

producing graduates who have gone on to make some of the

most polished and overproduced music on the American music

scene. The real reason why people either love or hate it

remains strangely elusive and difficult to define. Jam bands

have co-opted bluegrass, using it as a platform for extended

bouts of self-indulgent improvisation, only to come around

after hours of psychedelic exploration to zip through

updated versions of such classic standards as How

Mountain Girls Can Love.

It is hardly surprising that

Jerry Garcia loved bluegrass and originally aspired to be a

banjo player in Monroe’s band. Had he taken an interest in

klezmer music and played a clarinet, it is arguable that

Deadheads would have come to prefer klezmer over bluegrass.

Monroe himself characterized the genre as “Scottish

bagpipes and ole-time fiddlin’. It’s Methodist and Holiness

and Baptist. It’s blues and jazz, and it has a high lonesome

sound.” Its retrograde racist and misogynistic roots lie

deeply embedded in traditional English, Scottish, and Irish

ballads, dance tunes and reels, originally transported down

the Mississippi by French Canadian traders and Canuck fur

trappers. The style was further developed after WWII by a

number of exceptionally gifted musicians who played with

Monroe, including five-string banjo virtuoso Earl Scruggs

and scrupulous finger-picking guitarist Lester

Flatt.

Bluegrass generally features acoustic string

instruments and emphasizes the off-beat. Notes are

anticipated, creating the characteristic, accelerated level

of high octane playing, in contrast to more laid back blues

where they are more often played slightly behind the beat,

or “in the pocket.” As in jazz, instrumentalists take

turns playing the melody and improvising around it, while

the other musicians perform accompaniment, typified by tunes

called ‘breakdowns’ that are characterized by rapid tempos,

unusual instrumental dexterity, and complex chord changes,

as opposed to old-time music, in which all instruments play

the melody together, or one instrument carries the lead

throughout while the others provide accompaniment.

Three

main sub-genres are broadly discernible: in traditional

bluegrass, musicians play folk songs with traditional chord

progression on acoustic instruments; progressive bluegrass

groups like The Punch Brothers, Cadillac Sky, and Bearfoot

tend to employ electric instruments and import songs from

other genres, particularly rock & roll; while bluegrass

gospel employs Christian lyrics, soulful three and four-part

harmonies, and sometimes solo instrumentals. A more recent

development is neo-traditional bluegrass that typically

involves more than one lead singer, as exemplified by bands

such as The Grascals and Mountain Heart.

Emphasising an

unplugged sound, especially the unnerving twang of banjos

and fiddles, bluegrass performers have aadopted the scornful

sensibility of an ancient musical tradition handed down from

the distant mists of time. In reality, however, the genre is

only ten years older than rock ‘n’ roll. As performed by its

earliest practitioners, it was considered a radical

innovation in its time – much faster and more precise than

any of the old-time mountain music that preceded it. Some

celebrate its birth year around 1940, when Monroe made his

first recordings for RCA, while others prefer 1945, when he

hired Scruggs, whose three-finger banjo roll made the music

much leaner and more virtuosic than before. In any case,

Monroe’s musical modernism proved as revolutionary in

country music as the concurrent phase of bebop pioneers did

in jazz.

The progressive nature of Monroe’s music was

camouflaged by the conservative cast of his lyrics. His

music echoed the power of the radios and telephones that had

reached into isolated Appalachian communities and connected

them to the outside world. It also reflected the increased

velocity of the cars and trains that were liberating young

people from farms and small rural towns into Atlanta and

Northern industrial cities. The lyrics assuaged the

homesickness of people on the move by providing a

sentimental sense of nostalgia for a rapidly vanishing way

of life. Bands such as The Gibson Brothers, The Spinney

Brothers, and The Larry Stephenson Band ably fill this role,

taking classic Monroe recordings as a template to follow,

rather than an inspiration to change.

There are still

plenty of bands doing it Monroe’s way, spitting out

lyrical tales of heartache interspersed with rapid mandolin

and banjo breaks, but when Monroe ‘invented’ the genre, it

was genuinely outsider music compared to the sort of glossy

Bing Crosby/Perry Como/Tony Bennett crooning popular in

post-war America. From the late 1950s and well into the

seventies, many mid-Atlantic areas flourished with bluegrass

bands. It was an aggressive and emotional music mostly heard

mostly in bars where sawdust covered the floors and remained

stubbornly beyond mainstream acceptance, despite the

commercial success of soundtrack albums from The Beverly

Hillbillies to Bonnie and Clyde and

Deliverance.

America’s musical heritage remains a

racial minefield, however. Prejudice pops up regularly to

complicate tunes we would prefer simply to enjoy, in the

same way it feels weird these days to watch an old Mel

Gibson movie. Take Big Bend Gal, for instance, a

catchy fiddle-and-vocal number about a female field hand who

is ”the queen of the whole plantation” and includes such

lines as “There’s no use talking about the Big Bend Gal

who lives at the county line / For Betsy Jane from the

prairie plain just leaves them way behind.” Big Bend

Gal was first recorded in 1927 by the Shelor Family of

Virginia, who were white and sang it in a raw hillbilly

style with lines that put nowadays put a damper on the

festivities.

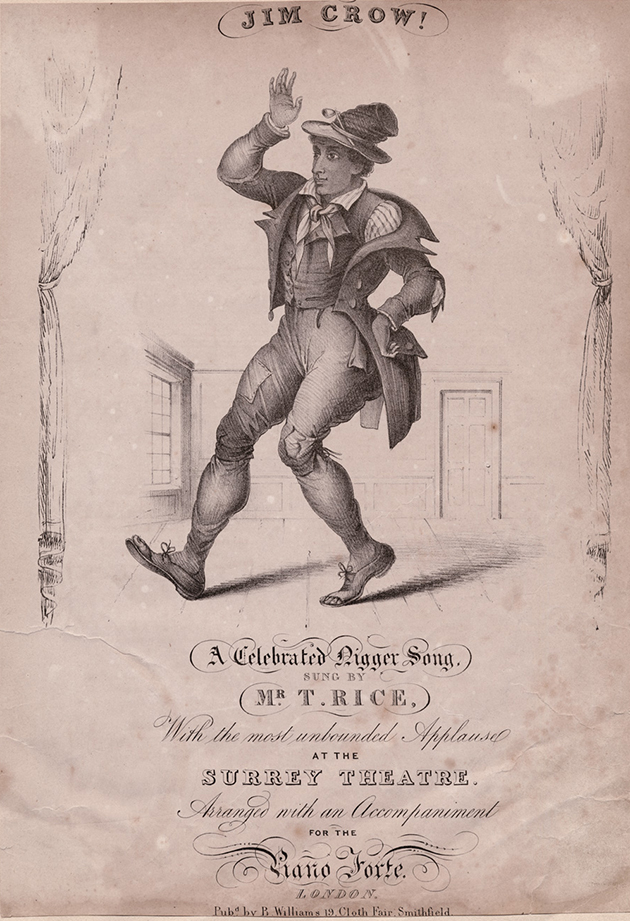

Jump Jim

Crow is another popular fiddle tune with a dubious

history whose refrain goes “Weel about and turn about and

do jis so / Eb’ry time I weel about I jump Jim Crow.” In

the early 1830s, a white actor named Thomas Dartmouth Rice

adopted the song and its eponymous trickster character for a

comedy act that would catapult him to international fame.

Donning rags and blackface, Rice performed send-ups of black

speech and culture, song and dance. He wrote endless new

verses for his signature ditty – corny slapstick humor with

the occasional social commentary:

And if de blacks should

get free,

I guess dey’ll fee some bigger,

An I

shall concider it,

A bold stroke for de

niggar.

Rice’s success paved the way for a wave of

mean-spirited blackface performers and the ‘Jim Crow’

moniker soon became synonymous with American apartheid. In

the post-bellum period, black entertainers also did

blackface routines for a time, before moving on to blues or

jazz-based vaudeville acts. “The first one or two

generations of black performers took those stereotypes to a

far deeper degree of racist imagery than even the white

performers did,” said Don Flemons, a black fiddler and

founding member of the Carolina Chocolate Drops who moved on

to a solo career in 2014 and has a passion for black cowboy

songs. Black performers often “subverted these images and

black audiences could tell,” but white minstrelsy evolved

into something “more sinister.”

According to

North Carolina historian David Gilbert, a century ago

blackface was “the only game in town … [black

entertainers] acted, sang, and performed in the few

caricatures available to them: the dandified, urban Zip Coon

and the slow-witted Sambo, to name the two most prominent

types. Often these ‘coon’ caricatures traded in razor

violence, lust, and gastronomical stereotypes like chicken

and watermelon. But these were the stereotypes of their day,

not just in minstrelsy, but in the advertising and consumer

culture.” Given the heavy baggage of all this history,

should white musicians feel conflicted about playing a

haunting instrumental like Mace Bell’s Civil War

March, knowing that it was written by a Texan fiddler

who served in the Confederate Army?

Lots of old songs

beloved by country and bluegrass audiences have similarly

complicated histories. Among the most notorious is

Dixie’s Land a tune usually credited to Ohio-based

showman Daniel Emmett, who founded one of the first

traveling blackface troupes during the 1840s. Dixie

became an unofficial Confederate anthem, with lyrics that

expressed nostalgia for a lifestyle based on the brutal

oppression of black people: “Oh I wish I were in the land

of cotton / Old times there are not forgotten.” Flemons

does not think the song is racist per se, “but how it’s

applied in the world – that’s a whole different thing.”

This fraught past is the reason why, in 2016, the University

of Mississippi banned its marching band from playing the

song at sporting events. The racist roots of the song was

too troubling even for a school that still styled itself

‘Ole Miss.’

The horrors of slavery and its aftermath are,

to quote the sideview mirror, closer than they appear.

History is the antidote to temporal parochialism, which

makes us think the only time is now, and geographical

parochialism, which makes us think the only place is here.

Prejudice “is still in our blood, it’s still in our

actions, it’s still in our Constitution – little fragments

that are left over and covered up by new laws,” Ben Hunter

said. “In the right context, it’s important to perform

Run, Nigger, Run – another slave song adopted by

white performers – ”because black and white people were

singing that song, but probably for different

reasons.”

“People are trying to find modern

sensibilities in stuff that was not built on modern

sensibilities,” said Flemons who performed an instrumental

version of Stephen Foster’s Ring, Ring de Banjo at

a Foster-themed event with the Cincinnati orchestra in 2015.

Foster’s racist lyrics are “absolutely unacceptable

nowadays,” he acknowledged, “and I would never think to

perform that song outside the context of that specific

show.” But these once-popular songs “are a document of

what happened” and failing to acknowledge that history

would “completely devalue the strength of how far we’ve

come.”

Slavery was foundational to British and American

prosperity and rise to global power. Sugar fast became

Britain’s largest import and the craze for it revolutionised

national diets, spending habits, and social life, not least

because of its association with that other newly fashionable

drug, tea. During the C18th, English consumption of of sugar

sky-rocketed from about four pounds per person per year to

almost twenty, roughly ten times as much as the French, who

preferred coffee. All this abundance, luxury, and so-called

domestic progress derived from the brutal exploitation of

huge numbers of enslaved African men, women, and children

across the Atlantic. As its defenders liked to stress,

slavery was hardly a new phenomena. It was taken for granted

in biblical and classical times, practised by virtually

every previous civilisation, and common in Africa itself,

but there had never been anything like the scale of

plantation culture that the British pioneered in the

Americas, where so many slaves were held in proportion to

the population of free people. In Virginia, which had by far

the the most enslaved people of the thirteen mainland

colonies, they made up roughly forty precent of all

pre-revolutionary inhabitants, but whites always remained in

the majority. As atrocious and barbaric as the treatment of

slaves was in North America, it was incomparably worse in

the West Indian sugar estates, which were not only the

largest agricultural businesses in the world, but also the

most destructive of human life.

Throughout the colonies,

speech, song, and music were all central to the culture of

enslavement. For both slave owners and the enslaved, spoken

and sung words simultaneously functioned not only as

representations, but also as performative speech action.

Their utterance was the most ubiquitous way in which the

boundaries between liberty and bondage were constantly

reinforced, negotiated, or contested. During the C18th,

“freedom of speech” (a concept previously associated

only with parliamentary debates) came to be seen as

foundational to all political liberty. Both colonial laws

and politics were transacted through verbal rituals like the

taking of oaths, the giving of evidence, or the making of

public speeches, from which women, slaves, and other lesser

humans (like Jews, Quakers, Native Americans, mulattos, and

free blacks) were to a greater or lesser extent excluded.

The precisely-drawn boundaries of this power to speak, to be

heard, and to silence others were frequently disputed within

the colonial population precisely because they were so

central to the meaning of freedom.

Speech and song were

also pivotal in C18th definitions of what it meant to be

human. Abolitionists claimed that the eloquence of slaves

proved their equal humanity, at a time when most whites took

it for granted that black utterances were inherently

inferior, even bestial. When the Scottish ‘Enlightenment’

philosopher David Hume set out to prove that whites were

intrinsically superior to all other “breeds,” he

confidently discounted “negroe” voices as nothing more

than brutish squawks. It is striking how much effort was put

into physically, as well as legally, silencing enslaved

people. As a young boy recently transported from the Guinea

Coast to a Virginia plantation in the mid-1750’s Olaudah

Equiano was terrified by the appearance of a black house

slave who moved around fixed in an iron muzzle, “which

locked her mouth so fast that she could scarcely speak; and

could not eat or drink.” Some slaveowners ordered such

equipment from London. Others, like the bookish young

Englishman Thomas Thistlewood, improvised their own horrific

gags. He also recorded in his diary 3,852 acts of rape with

almost 150 enslaved women. Apart from the thoroughness of

his record-keeping, Thistlewood was entirely typical, even

relatively restrained, in his behaviour. Freedom of speech

and the power to silence may have been pre-eminent marker of

white liberty, but at the same time slavery depended on

dialogue and slaves could never be entirely muted. Even in

conditions of extreme violence, stories and songs remained

ubiquitous, ephemeral, and potentially transgressive.

Moreover, African slaves themselves came from societies in

which oaths, orations, and invocations were laden with great

potency, both between people and as a connection to the

spirit world.

The reality is that music, like sport, is

never politically neutral. Both its form and content can

demand progressive and revolutionary change or remain

profoundly conservative, supporting the social status quo

ante. Just ask the (now mercifully defunct) Black and White

Christy Minstrels, or the Springboks, or soccer fans in

Glasgow, Manchester, and Liverpool who choose to support one

of two soccer teams along largely ideological lines, one

predominantly supported by the Catholic community, the other

resolutely Protestant. Or, better yet, ask the NBA, which

recently concluded its season not only with the Lakers’

successful championship run, but also the full endorsement

of a mass political movement by teams, players, and fans

alike.

As it is with sport, so it is with music, the most

immediately moving and affective of all artistic modalities.

The sort of music we like to listen to and support has

political ramifications and ideological implications. In

these days of ‘Black Lives Matter,’ when black folks are

still getting shot in the back at point blank range and

synagogues across the Southern states are routinely defaced

by swastikas, they reflection of moral values. Country music

harks back to the ultra-conformist Eisenhower era, a simpler

time when coloured folks knew their place and red-necked,

‘good ol’ boys’ drove around sporting gun-racks in their

pick-up trucks and looking for suitably sturdy trees from

which to hang their “strange fruit.”

It is crucial

that Americans decisively reject this caudillo model of

one-man rule in the upcoming election, if they are to

restore some of the liberal democratic norms that this

huckleberry clown has so wantonly and consistently trashed.

A landslide would certainly provide a cautionary tale, but

making the election solely about ‘wokeness’ is to ignore

many other issues that also need to be taken into account,

such as climate change and access to affordable universal

healthcare, let alone Trump’s mental and emotional

instability in the White House, where thoughts seem to drift

randomly around like tumbleweed on Main Street. Comparisons

with previous Republican presidents are salient. Like

Reagan, Trump is an authoritarian and callous poseur who

hasn’t hesitated to send in armed police and the National

Guard to break up civil protests. While more than 89,000

people died of Aids over seven years under Reagan’s

administration, however, Covid deaths in the US over seven

months under Trump are 225,000 and rising fast. Even

a radical, bipartisan, and cross-party realignment of

government institutions would at best move towards a

restoration of pre-Trump America.

The US desperately needs

to address systemic structural inequalities, if it is to

survive what is inevitably coming next. In January, a gun

rally in Richmond, Virginia, attracted thousands of militia

members and extremists carrying semi-automatic assault

rifles, NRA members, and armed Trump supporters from across

the country – all mixing together in large crowds.

What

are these people so afraid of? Against whom are they trying

to protect themselves?

The answer is all too apparent –

not only such well-known victims of gun violence as Trayvon

Martin, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd, but also Walter

Wallace, a mentally disturbed young man who was shot more

than ten times by a Philadelphia police officer only last

week. Such repeated and despicable patterns of behaviour are

based on deeply ingrained fears and prejudices with several

hundred years of back story.

Sporting a fedora and

grizzled love patch, Klein is well positioned to undercut

the music’s more questionable aspects, peppering the

playlist with Northern Union, Italian revolutionary, and Bob

Marley protest songs. He carved a crisp and clean path

through the sort of gut-bucket hoe-downs more typically

associated with the unfortunate inhabitants of trailer parks

– poor, white, and predominantly found in the most

impoverished regions of the US that have experienced the

ravages of coal-mine closures, the collapse of public

education and consequent mass illiteracy, and the

devastating effects of prescription opiate addiction. These

Southern and Midwestern states are the rabid heartland of

Bible-bashing and heavily-weaponised Trump supporters.

Without any effort at explanation or historical

contextualisation, such enthusiasm for a musical genre

steeped in racial and misogynistic stereotypes runs the risk

of being seen as just another a patronising affectation,

like the Tom Waits hat and strange facial hair. Fortunately

Klein’s solid and well-informed performance was pitch

perfect and provided exactly the right equilibrium. The

audience – which ranged from toddlers to grannies –

certainly appreciated the band’s toe-tapping antics, which

were neatly balanced out by some soulful harmony singing on

the slower numbers. A little fiddle can go a long way, but

mercifully there were no klezmers or accordions in

evidence.