More than five million people became first-time gun owners during the pandemic as gun sales to the community rose by about 43%

Vivian Moon, a real estate agent and artist, had never felt particularly afraid as a woman living alone in Buena Park, a small California city outside Los Angeles. But when violent attacks against Asian women and seniors increased across the US early last year, she became disillusioned with the police’s ability – and willingness – to protect people who looked like her.

So, like many other Americans of Asian descent, she decided to buy a gun. “I realized I have to take ownership of how I want to live my life,” said Moon, 33.

In the year since, Moon said she’s made an effort to reach out and teach her friends, many of whom are women of color, about gun safety. As a Korean woman who grew up in the 1990s, Moon is also inspired by the legacy of the Los Angeles uprising and the armed Korean immigrants who defended their businesses on rooftops when riots broke out in South Central. “Back then Korean Americans took a stand and took their safety into their own hands,” she said.

Gun ownership rates soared to record heights during the pandemic, as more than 5 million people became first-time owners, according to the trade organization National Shooting Sports Foundation (NSSF). That includes Asian Americans. As videos of anti-Asian violence began flooding social media and cable news, gun sales to Asian Americans, though still significantly lower than those of other racial groups, rose by an estimated 43%.

Asian Americans who experienced or witnessed increased acts of racism at the start of the pandemic were more likely to buy firearms for self-defense, according to a new peer-reviewed study from the University of Michigan and Eastern Michigan University. More than half of those who purchased a gun are first-time owners.

“Racism is like a time bomb that causes stress and anxiety, which increases people’s intention to buy firearms,” said Tsu-Yin Wu, the lead researcher and director of EMU’s Center for Health Disparities Innovation and Studies. “Not only are people carrying it on more days, they’re also carrying it more than 50% of the time.”

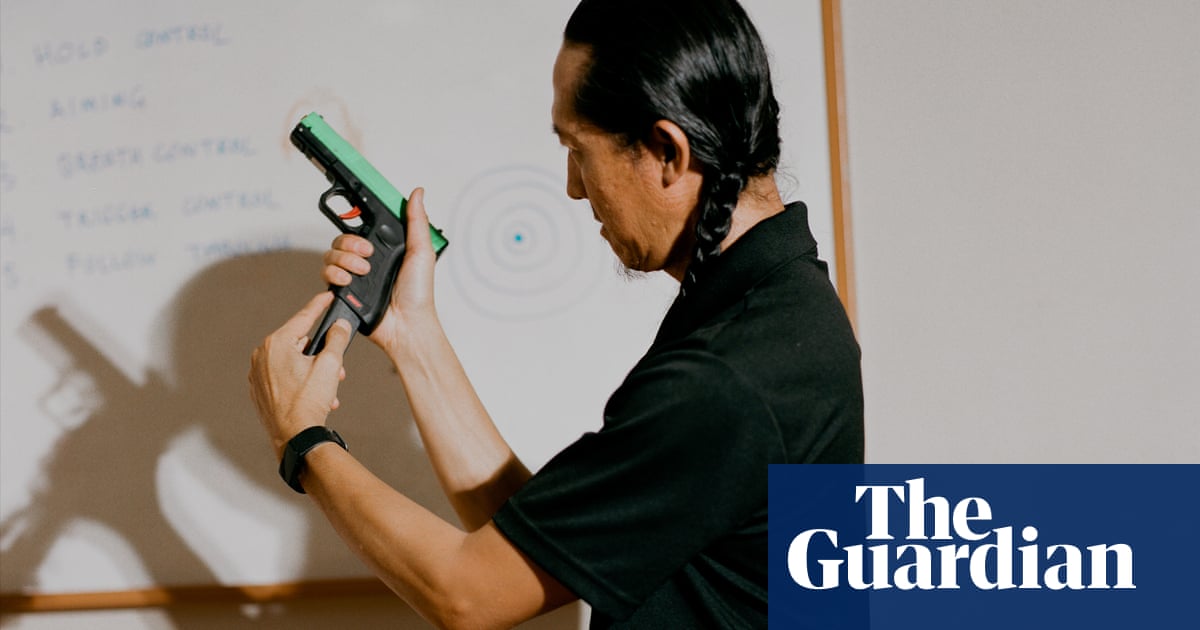

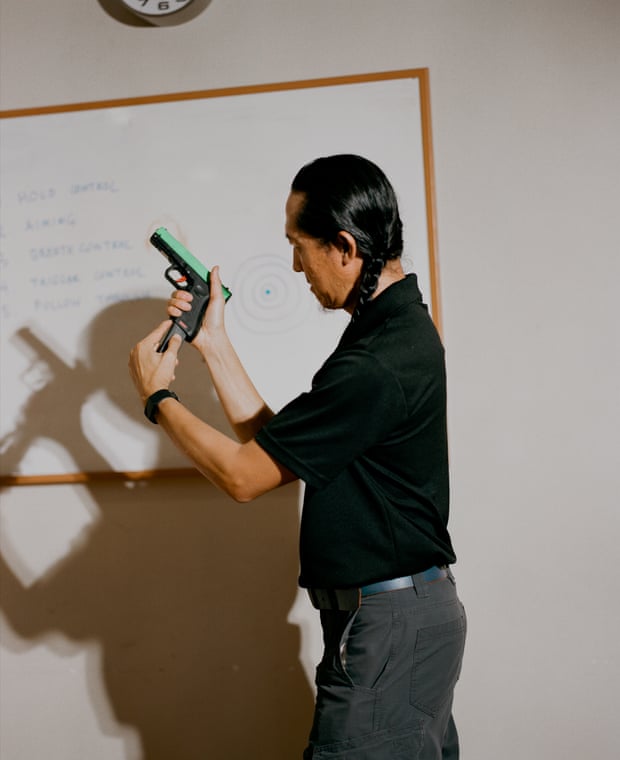

During the pandemic, a host of Asian American affinity groups have emerged in southern California to provide resources and a sense of community to new gun owners. Tom Nguyen founded LA Progressive Shooters to provide firearms education to people of color, after seeing a “massive increase in first time gun owners”, particularly single women and queer people.

Nguyen, who leads introductory classes on firearm storage and shooting, said the pandemic has been a “lightning rod moment” for Asian Americans and other marginalized groups of people who previously have held an ambivalent or fearful attitude toward guns.

“Many folks are intimidated by these conservative, white dominated spaces that don’t seem very friendly to them,” he said. “So the gun industry has a long way to go in terms of addressing more diverse segments of our population who are interested but feel forgotten or ignored.”

At the same time, there are documented risks associated with rising household gun ownership, including higher rates of homicides and suicides. An April study from the Annals of Internal Medicine, which surveyed more than a half million Californians, found that people who live with handgun owners are shot to death at a higher rate than those who live in gun-free homes. Women made up 84% of victims.

Data on firearm use among Asian Americans is limited, as the group, which comprises about 7% of the US population, has historically had low gun ownership rates. From 2015 to 2019, FBI’s Supplementary Homicide Report documented 37 justifiable firearm homicides committed by Asian Americans. By contrast, more than 3,000 Asian Americans died in firearm suicides, homicides and accidental shootings during the same time period. Among Asian American youth, firearm suicide rate rose by 71% over the last decade – the largest growth of any racial or ethnic group, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The National Rifle Association, meanwhile, has taken the pandemic as an opportunity to more aggressively market guns to Asian Americans. Varun Nikore, executive director of AAPI Victory Alliance, said it’s opportunistic for gun manufacturers to court the group given the existing data linking rising gun ownership rates to firearm-related deaths.

“They’re directly exploiting our pain and trauma by doing direct and targeted campaigns to increase the amount of gun ownership in communities that have not typically had it,” he said. “And they’re doing it just for profit.”

Some gun rights activists, though, see the current surge as the dismantling of historical barriers, since Asians on the west coast were not always allowed to practice their Second Amendment rights. In 1923, California passed a law denying non-citizens the right to possess concealable firearms. That ruled out Chinese immigrants, a majority of whom were barred from naturalizing by the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.

Asian Pacific American Gun Owners Association, a non-partisan group formed last March amid a rise in anti-Asian hate crimes, publishes educational materials regarding gun safety and usage in multiple Asian languages. Chris Cheng, a board member and winner of History Channel’s Top Shot competition, said that the civil unrest and relentless scapegoating over the past couple of years have pushed many Asians to arm up for the first time in their lives.

“You see all this eroding trust in our public institutions and our criminal justice system,” Cheng said, citing the January 6 insurrection and calls to defund the police.

Cheng also said the media’s coverage of the gun debate fixates on homicides, which comprise only one-third of firearm deaths, and overlooks data on defensive gun use. A widely used but contested study cited by the CDC estimates that guns are used defensively between “60,000 to 2.5m” times a year.

For some Asian Americans, the peace of mind that guns can bring outweighs their potential for harm.

Nathan Tiep, 42, and his wife are in the process of buying their first gun after seeing news coverage of home invasions near their neighborhood of Boyle Heights. Tiep, the son of Cambodian refugees, grew up in Long Beach in the 1990s, where deadly clashes between Asian and Latino gangs made him numb to gun violence. “We knew what guns can do but weren’t afraid of it,” he said.

More so than the surge in attacks against Asians, Tiep said his decision to buy a gun was shaped by the Black Lives Matter protests during the pandemic, which have shattered his trust in law enforcement.

“The past few years have brought to light how the police are with people,” he said. “You’ve seen people get shot and killed by police. Do you really trust that they will serve and protect us?”